Passages of Learning English Practice

- April 23, 2025

- no comments

Warning: Trying to access array offset on false in /home/u935310590/domains/bafel.co.in/public_html/blog/wp-content/themes/bafels/content.php on line 38

Passage 1 – COMPLEX (formerly Easy)

The Psychology of Smiling in Interpersonal Communication

In professional communication, particularly in cross-cultural contexts, the strategic use of a smile can either reinforce trust or, paradoxically, raise suspicions, depending on the audience’s cultural schema. For instance, in some Western cultures, smiling is associated with openness and sincerity, while in others, such as Japan or Russia, excessive smiling can be interpreted as superficial or insincere.

Furthermore, in customer service and negotiation settings, a controlled smile functions as a non-verbal cue indicating receptiveness and psychological safety. It reduces perceived social distance and invites reciprocal engagement. Studies in affective science suggest that even virtual or phone-based communication can be modulated by tone shaped through a smile, demonstrating the cross-modal influence of facial expression on vocal prosody.

However, not all smiles are created equal. Duchenne smiles, which engage both the mouth and eyes, are more likely to be perceived as authentic, whereas non-Duchenne smiles may be misread. The ability to differentiate between these nuances is crucial for learners of English aiming to develop soft skills alongside linguistic competence.

Mastering the appropriate deployment of a smile, therefore, requires emotional intelligence, situational awareness, and a sensitivity to intercultural norms. It exemplifies how seemingly minor non-verbal behaviors can carry disproportionate communicative weight.

Passage 2 – COMPLEX (formerly Medium)

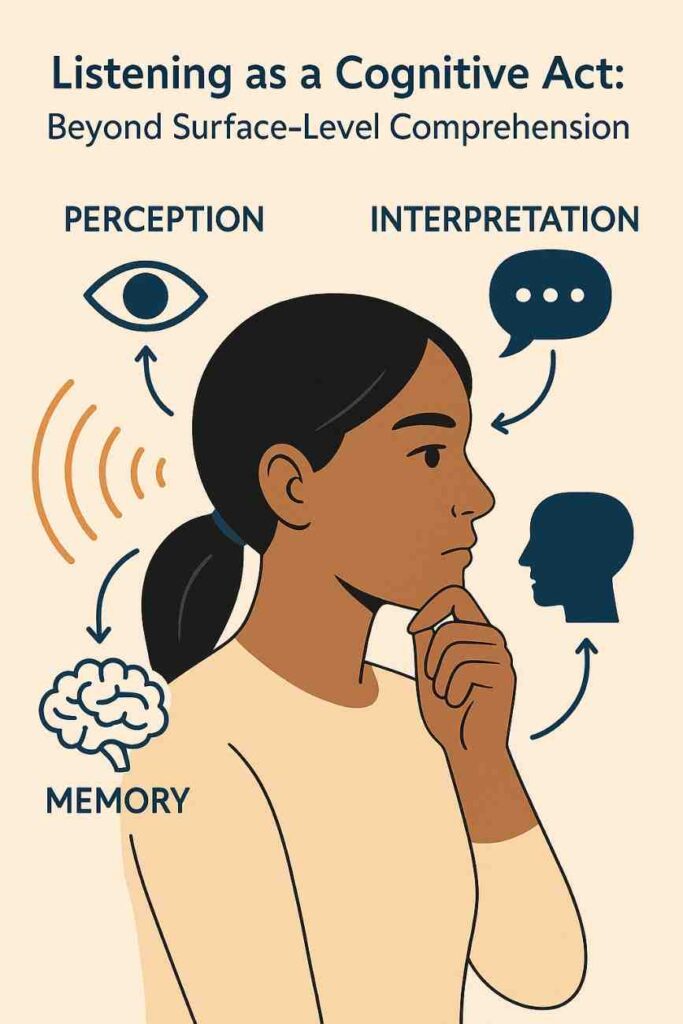

Listening as a Cognitive Act: Beyond Surface-Level Comprehension

In the realm of effective communication, listening is often mischaracterized as a passive process, merely requiring the auditory decoding of spoken language. However, true listening is an active, cognitively demanding skill that integrates perception, interpretation, memory, and response formulation in real time.

Active listening involves the listener’s engagement with both verbal and non-verbal signals, necessitating mental agility and empathetic alignment with the speaker’s perspective. It requires the suppression of internal dialogue and the intentional focusing of attention—capacities which are often compromised in our current environment of digital hyperstimulation and shortened attention spans.

Research in psycholinguistics underscores the fact that the brain processes spoken language in “chunks,” utilizing working memory to retain and synthesize these segments while simultaneously predicting upcoming content. This dual-processing is what allows skilled listeners to paraphrase, clarify ambiguities, and ask insightful questions that reflect comprehension.

Moreover, effective listeners are adept at decoding paralinguistic elements—tone, pacing, pitch—as well as gestural cues that modify semantic intent. Misalignment between verbal and non-verbal communication is often a more reliable indicator of deception or emotional distress than the words themselves.

From an educational standpoint, cultivating high-level listening skills improves not only communication outcomes but also enhances intercultural sensitivity, critical thinking, and interpersonal rapport. Thus, teaching listening should extend beyond pronunciation and vocabulary to include metacognitive strategies and awareness of cognitive biases.

Passage 3 – COMPLEX (formerly Difficult)

Linguistic Economy and the Imperative of Clarity in Professional Writing

In an era characterized by rapid information dissemination and global interconnectedness, clarity and brevity have emerged as hallmarks of professional English writing. Linguistic economy—the principle of conveying maximum meaning using minimum words—is not merely a stylistic preference but a pragmatic necessity.

Clarity in communication reduces cognitive load on the reader, minimizes the risk of ambiguity, and enhances decision-making efficiency, particularly in contexts where precision is critical—such as legal writing, academic discourse, and corporate communication. This clarity, however, must not be mistaken for oversimplification. The challenge lies in distilling complex ideas into accessible prose without sacrificing nuance.

Precision requires the exclusion of redundant modifiers, nominalizations, and passive constructions unless rhetorically warranted. Consider the phrase: “The decision was made by the committee after deliberation.” It is more efficient and impactful to write: “The committee decided after deliberating.” This not only shortens the sentence but also energizes it through active structure.

Furthermore, vague quantifiers—“some,” “many,” “a few”—must be replaced with specific data wherever possible. Writers who employ concrete terminology project credibility, as specificity is often equated with authority and trustworthiness in professional settings.

Importantly, clarity also encompasses the logical sequencing of ideas and syntactic consistency. Paragraph cohesion, thematic unity, and transitional fluency are as vital as lexical choice. Ultimately, professional writing is not about displaying verbal ornamentation but ensuring that the reader arrives at the intended message with minimal interpretive friction.

Passage 4 – COMPLEX (formerly Difficult)

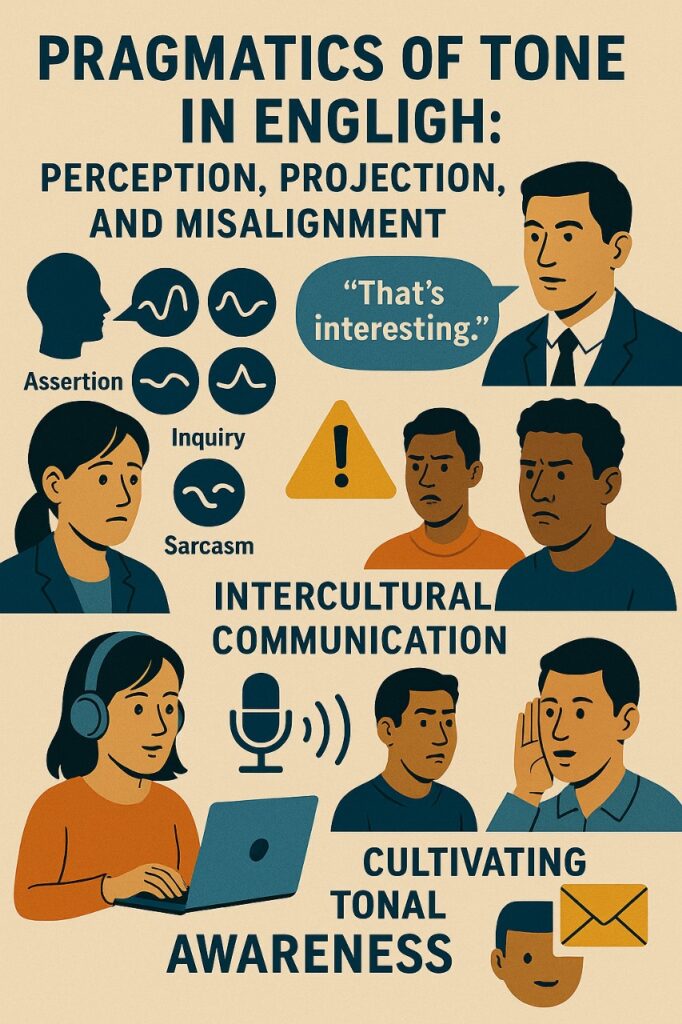

Pragmatics of Tone in English: Perception, Projection, and Misalignment

Tone in spoken English transcends its linguistic definition as the modulation of pitch. It embodies the speaker’s affective stance, relational intent, and social alignment, all of which are crucial for pragmatic competence. Yet, it remains one of the most elusive elements for non-native speakers to master.

The same lexical content, when uttered with different tonal patterns, can signify assertion, inquiry, sarcasm, or even passive aggression. For example, the statement “That’s interesting,” when said with a flat tone and raised eyebrows, may denote skepticism rather than curiosity. Learners must therefore be attuned not only to phonemic details but also to prosodic contours and contextual subtext.

In intercultural communication, tonal misalignment can result in unintended rudeness, perceived disinterest, or an impression of over-familiarity. Furthermore, in professional domains such as customer service, legal advising, or healthcare, tone has a direct bearing on client satisfaction and ethical rapport.

To cultivate tonal awareness, learners must develop both production and perception skills. Shadowing native speakers, recording and analyzing speech samples, and receiving feedback from trained professionals are essential. In advanced pedagogy, this process is termed “prosodic immersion.”

Moreover, the role of tone extends into written digital communication. Email etiquette, for instance, requires strategic modulation of tone through syntax, punctuation, and lexical choice. Misjudging tone in a business email can undermine authority or create relational tension, particularly in high-context communication cultures.

Passage 5 – COMPLEX (formerly Difficult)

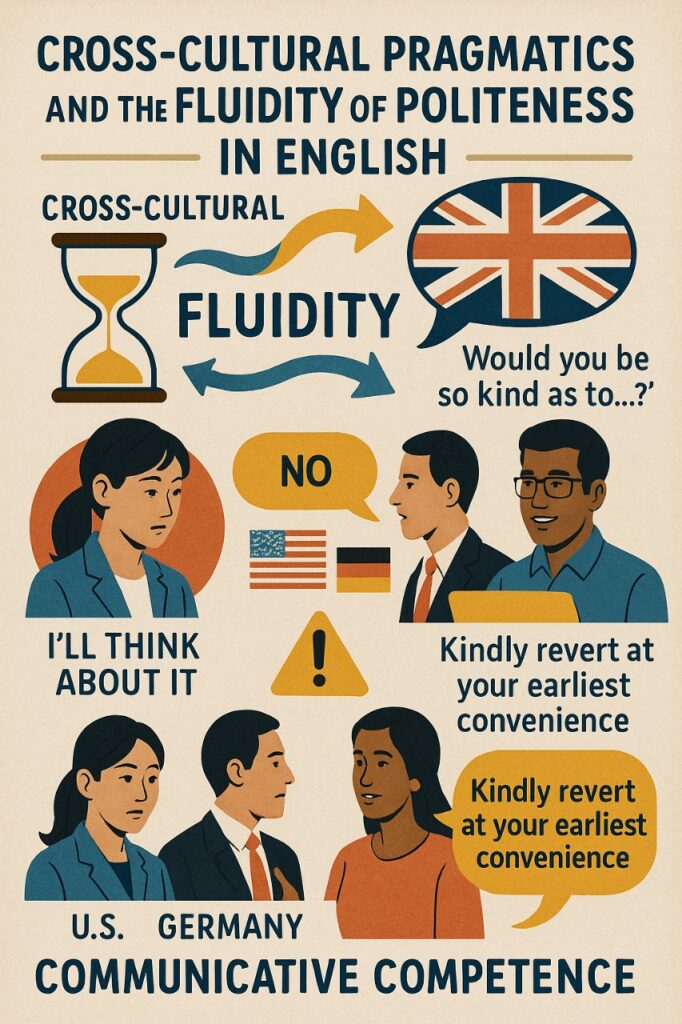

Cross-Cultural Pragmatics and the Fluidity of Politeness in English

Politeness, often assumed to be universal, is in fact a highly context-dependent and culturally variable construct. In English communication, politeness strategies are not static rules but fluid, adaptive responses informed by power dynamics, cultural expectations, and situational intent.

For example, in high-context cultures like Japan or Korea, indirectness and deference are integral to maintaining face. Saying “I’ll think about it” might imply a polite “no.” Conversely, in low-context, task-oriented cultures such as the United States or Germany, direct refusals are often appreciated for their clarity and honesty.

English, as a global lingua franca, has absorbed politeness norms from multiple traditions. British English leans toward euphemistic and highly mitigated speech acts (“Would you be so kind as to…?”), whereas American English favors straightforward yet courteous requests. The Indian English politeness register may incorporate honorifics and idioms rooted in local languages, such as “kindly revert at your earliest convenience.”

Pragmatic failure—the misapplication of politeness norms—can result in miscommunication, offense, or the appearance of arrogance. For instance, overusing imperative forms (“Send me the file now”) in a hierarchical setting may be perceived as disrespectful, even if no offense was intended.

To navigate this complexity, learners must not only master grammar and vocabulary but also develop metapragmatic awareness: the ability to reflect on and adjust one’s speech strategies in real time. This includes understanding when to hedge, how to soften requests, and when brevity might be seen as brusqueness.

In sum, achieving communicative competence in English requires cultural dexterity, not just linguistic fluency.

Contact Us Now:

Visit BAFEL Head Office:

A-56 Ground Floor, Sector 7, Block A, Palam Extension, Dwarka, Delhi, 110075

Dwarka Centre Google Maps: Get Directions

Call Central Customer Care: +91-9212779991

WhatsApp Us[ninja_form id=1]

SEARCH THIS SITE

- PG in Ramphal Chowk Dwarka Sector 7 – Why BAFEL PG Is the Top Choice

- Single Room PG in Dwarka Sector 7 Ramphal Chowk – Why BAFEL PG Is the Best Choice

- Work as a Nurse in Jordan – Earn up to ₹85,000/Month | BAFEL Overseas Placement

- Dreaming of a Nursing Career Abroad? Start Your Journey in Qatar.

- Master IELTS with Confidence — Join BAFEL Dwarka’s Morning Batch (8:30 AM – 2:30 PM)

- Spoken English Course | Speak Fluently and Confidently | Morning Batch (8:30 AM – 2:30 PM)

- Enroll in ChatGPT Course in Dwarka Sector 7, Ramphal Chowk – Learn from IIT Delhi Certified Experts!

- Join Alka Didi's online collectivity using these simple steps

- अलका दीदी की ऑनलाइन सामूहिकता में जुडने के लिए यह सिंपल स्टेप्स

- Kya Non-Veg Khana Galat Hai? Spiritual Drishti se Shri Mataji ka Margdarshan